Supporting First Language Learning for Children with Different Abilities: Pedagogical Practices, Policy, and Ongoing Challenges

By Eden Khaw

First language development is a foundational aspect of early childhood, underpinning children’s communication, learning, and social participation. The early years, particularly from birth to six, represent a critical period for language acquisition, during which children rapidly expand their vocabulary and communicative competence (Gleason and Ratner, 2022; NCCA, 2016). However, not all children experience language development in the same way. Children with different abilities, including those with developmental delays, dyslexia, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), or global developmental delay, often face additional challenges in acquiring their first language (NCSE, 2019; Nouraey, Ayatollahi and Moghadas, 2021).

Early childhood educators therefore play a pivotal role in creating inclusive, language-rich environments that support all learners. My research explores educators’ perspectives on effective pedagogical practices, the role of curriculum and policy, and the challenges faced when supporting first language learning for children with different abilities in preschool settings.

Effective pedagogical practices for first language learning

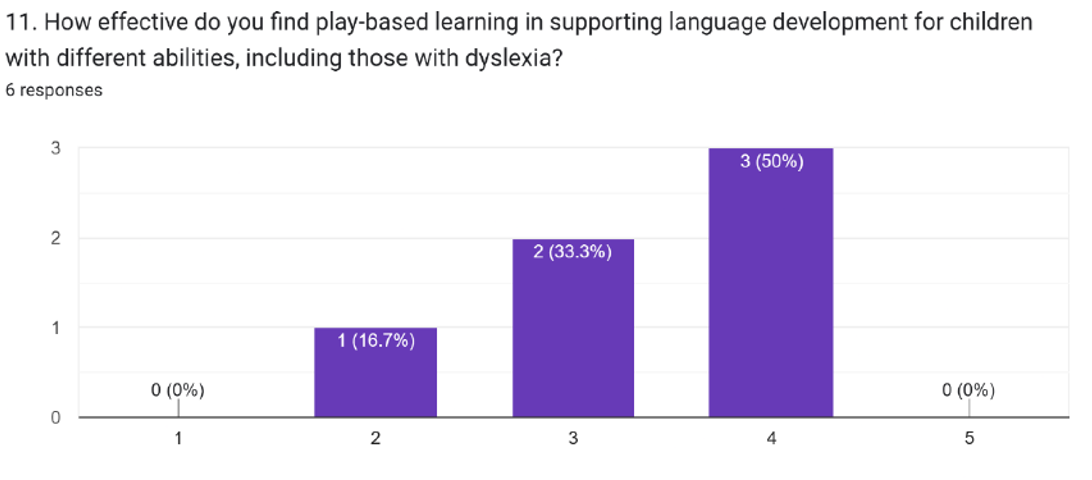

Research consistently highlights the importance of play-based learning and language-rich environments in supporting first language development. Play-based approaches encourage meaningful interaction, allowing children to develop communication skills naturally through social engagement, exploration, and shared experiences (Taylor and Boyer, 2020). For children with different abilities, these approaches are particularly effective when combined with developmentally appropriate practice, individualized instruction, and responsive adult support (Cade, 2023).

Figure 4.3 The effectiveness of play-based learning in supporting language development

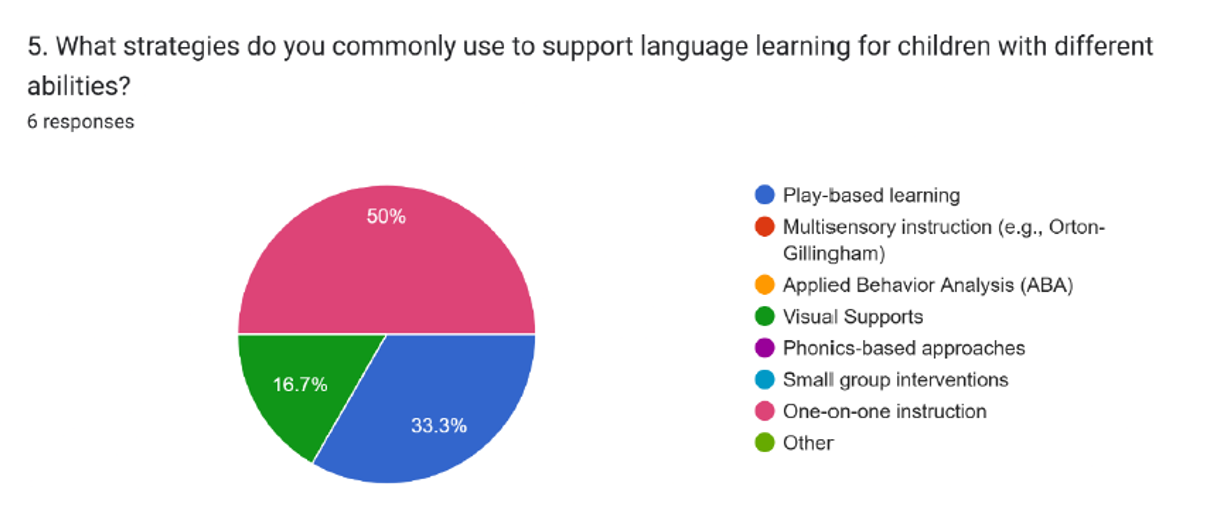

Scaffolding is a key pedagogical strategy identified in the literature. By adjusting the level of support based on a child’s current abilities, educators can gradually promote independence, confidence, and active language use (Hong, Shaffer and Han, 2017). The use of both verbal and non-verbal communication, such as gestures, visual supports, and modelling, further strengthens children’s engagement and understanding, particularly for those who experience difficulties with expressive or receptive language.

Inclusive pedagogical practices also emphasise the importance of knowing the child. When educators are attuned to individual needs, strengths, and interests, they are better positioned to adapt teaching strategies that support first language acquisition while fostering a sense of belonging and participation (Titova et al., 2021). These practices not only benefit children with different abilities but enhance language learning opportunities for all children within the classroom.

Figure 4.5 Strategies being used to support language learning for children with different abilities

Curriculum and policy influences on language learning

Curriculum frameworks and policies play a significant role in shaping how first language learning is supported in early childhood settings. In Ireland, Aistear and Síolta promote language development through play-based, inclusive, and child-centred approaches, emphasising the importance of rich interactions and responsive environments (NCCA, 2016). These frameworks align closely with principles of inclusive education and recognise language learning as an active, social process.

Policy initiatives such as the Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs (EPSEN) Act (2004) further reinforce the right of children with special educational needs to be supported within inclusive settings. However, research indicates that gaps remain between policy intentions and everyday practice. Limited resources, inconsistent implementation, and insufficient guidance on individualized language interventions can reduce the effectiveness of these policies for children with different abilities (Arduin, 2013; Kenny, McCoy and Mihut, 2020).

International comparisons, including Singapore and Canada, show similar tensions. While inclusive curriculum frameworks exist, their impact is often constrained by academic pressures, non-mandatory implementation, and reliance on external services rather than classroom support (Ang, Lipponen and May Yin, 2021; Cade, 2023).

Challenges faced by educators

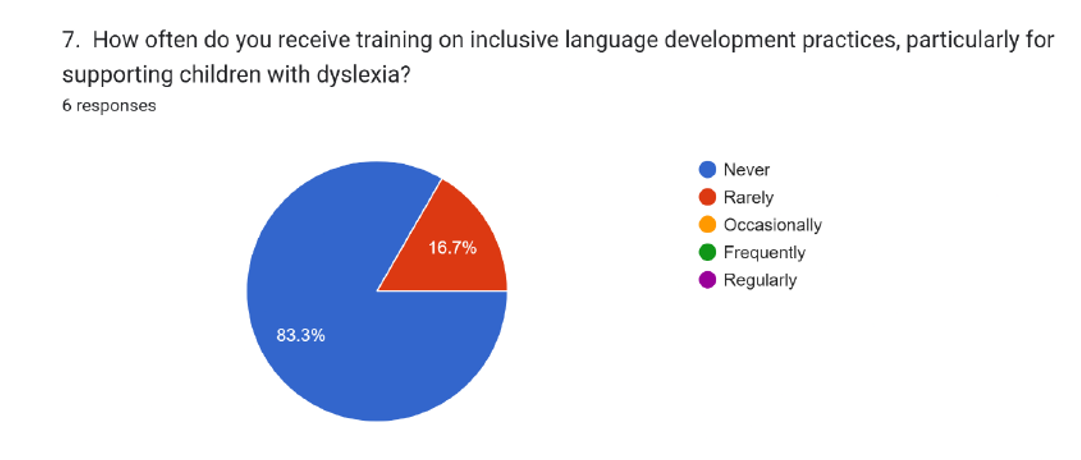

Despite strong commitment to inclusion, educators face persistent challenges when supporting first language learning for children with different abilities. Limited training, time constraints, and restricted access to specialist support are frequently reported barriers (Scanlon and McGilloway, 2006). Many educators express a need for ongoing professional development in areas such as language intervention strategies and differentiated instruction to meet increasingly diverse needs within inclusive classrooms.

Figure 4.4 The frequency of educators receiving training on inclusive language development practices

Resource limitations can also affect the amount of individualized attention children receive, particularly in mainstream settings where support staff may be shared across multiple learners (Rose and Shevlin, 2020). These challenges can leave educators feeling underprepared, despite their willingness to implement inclusive and responsive language practices.

Conclusion: Moving forward

Supporting first language learning for children with different abilities requires a sustained and balanced focus on effective pedagogical practice, inclusive curriculum frameworks, and meaningful policy implementation. Educators play a central role in fostering language development through play-based, language-rich environments, responsive scaffolding, and flexible approaches that recognise each child’s individual strengths and needs. However, even the most committed educators cannot work in isolation. Their ability to support children effectively is closely linked to access to appropriate training, sufficient time, and adequate resources.

There is no single or simple answer to the question of how educators can best support children’s first language learning. What is clear, however, is the need for continued reflection, collaboration, and research. Further research is essential to examine how existing curricula and policies can more effectively accommodate children with different abilities and how educators can be better supported in translating inclusive principles into everyday practice. By deepening our understanding of educators’ experiences, this research seeks to contribute to the ongoing development of inclusive early childhood environments—ones in which all children are genuinely supported to communicate, participate, and thrive.

References

Ang, L., Lipponen, L. and May Yin, S.L. 2021. Critical reflections of early childhood care and education in Singapore to build an inclusive society. Policy Futures in Education, 19(2), pp. 139–154. doi: 10.1177/1478210320971103.

Arduin, S. 2013. Implementing disability rights in education in Ireland: an impossible task. Dublin University Law Journal, 36, pp. 93–126.

Cade, J. 2023. Child-centered pedagogy: guided play-based learning for preschool children with special needs’, Cogent Education, 10(2). doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2023.2276476.

Gleason, J.B. and Ratner, N.B. 2022. The development of language. Plural Publishing.

Hong, S.B., Shaffer, L. and Han, J. 2017. Reggio Emilia inspired learning groups: relationships, communication, cognition, and play, Early Childhood Education Journal, 45(5), pp. 629–639. doi: 10.1007/s10643-016-0825-6.

Kenny, N., McCoy, S. and Mihut, G. 2020. Special education reforms in Ireland: changing systems, changing schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2020.1821447.

National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA). 2016. Enhancing language 3-6 years. Available at: https://www.aistearsiolta.ie/en/nurturing-and-extending-interactions/resources-for-sharing/enhancing-language-3-6-years-.pdf

National Council for Special Education (NCSE). 2019. Children with special educational needs: information for parents. Available at: https://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Web-Ready-03178-NCSE-Children-SEN-InfoBook-Parents2-Proof17-VISUAL-ONLY.pdf

Nouraey, P., Ayatollahi, M.A. and Moghadas, M. 2021. Late language emergence. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal [SQUMJ], 21(2), pp. e182–e190. doi: 10.18295/squmj.2021.21.02.005.

Rose, R. and Shevlin, M. 2020. Support provision for students with special educational needs in Irish primary schools. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 20(1), pp. 51–63.

Scanlon, G. and McGilloway, S. 2006. Managing children with special needs in the Irish education system: a professional perspective. REACH Journal of Special Needs Education in Ireland, 19(2), pp. 81–93.

Taylor, M.E. and Boyer, W. 2020. Play-based learning: evidence-based research to improve children’s learning experiences in the kindergarten classroom. Early Childhood Education Journal, 48(2), pp. 127–133. doi: 10.1007/s10643-019-00989-7.

Titova, O., Bratkova, M., Karanevskaya, O., Gravitskaya, E. and Barbakadze, I. 2021. Implementation of an individual educational route in inclusive practice, SHS Web of Conferences, Les Ulis, France: EDP Sciences. doi: 10.1051/shsconf/20219801019.