Holding Onto Childhood: Slow, Relationship-Centred Care in a World of Rapid Transitions

By Georgina Young

Childhood today feels different.

Children are navigating more transitions, earlier and more often — between home and setting, between caregivers, routines, expectations, and emotional demands. Even very young children are moving through a world that feels increasingly fast-paced, stimulating, and outcome-driven.

As early years educators, we often feel this pressure too. Pressure to prepare children for what comes next. Pressure to ensure readiness. Pressure to keep up — to go bigger, go faster, do more. And yet, both in my professional practice and as a parent, I’ve found myself repeatedly coming back to the same quiet question: what if what children need most during times of transition is to be slowed down, not sped up?

My practice-based inquiry explores how slow, relationship-centred early years practice can support children’s emotional wellbeing in a period of accelerating societal, developmental, and environmental change. It is rooted in everyday observations — not formal research — and shaped by lived experience, reflective practice, and deep relationships with children and families.

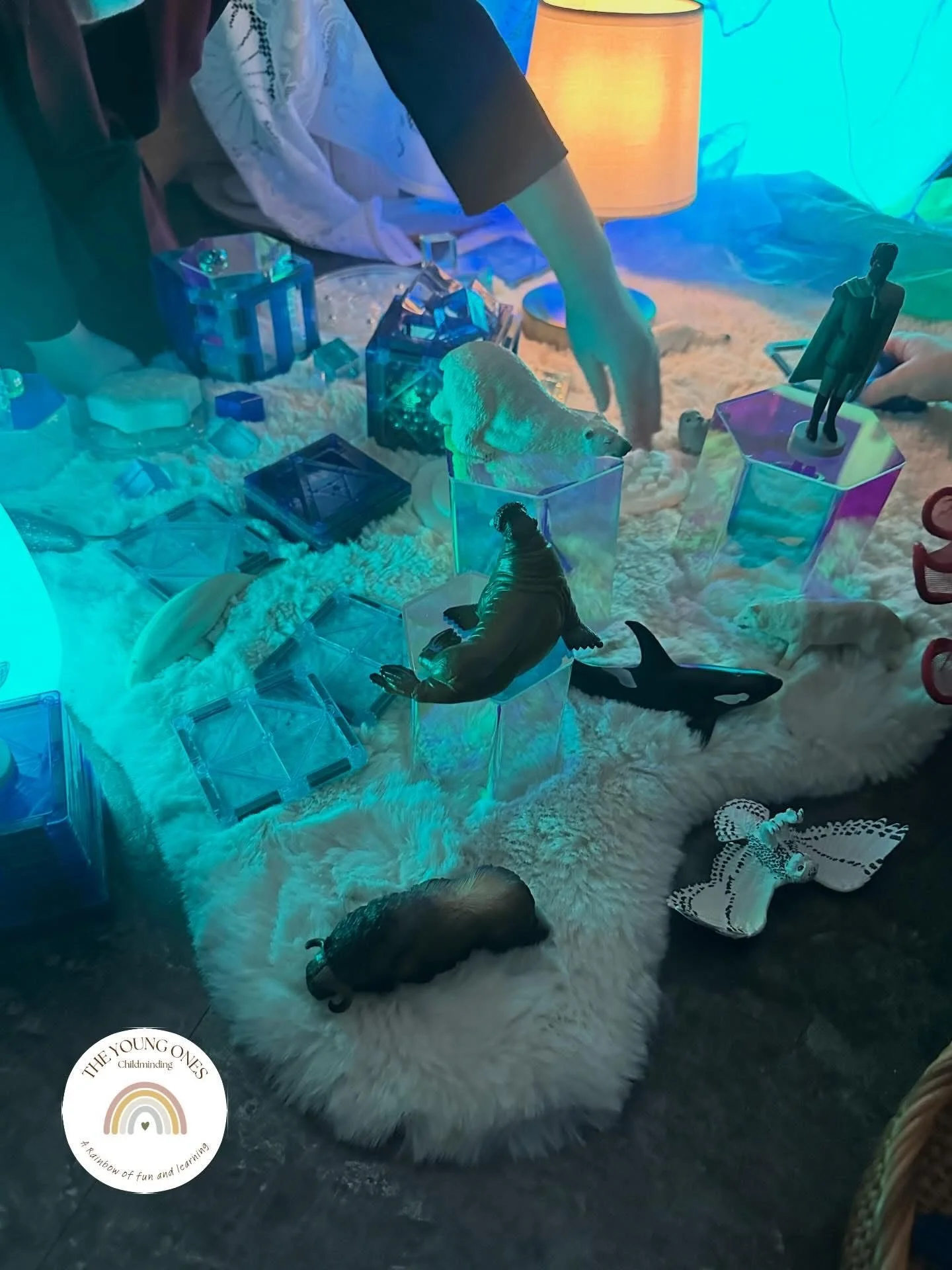

When learning unfolds at an unhurried pace, within secure, attuned relationships, children often show deeper engagement, greater emotional regulation, and growing confidence. Child-led, schema-informed play becomes a powerful way for children to make sense of their world. Repeated patterns of play — transporting, enclosing, positioning — are not simply activities, but meaningful processes through which children process change, uncertainty, and emotion.

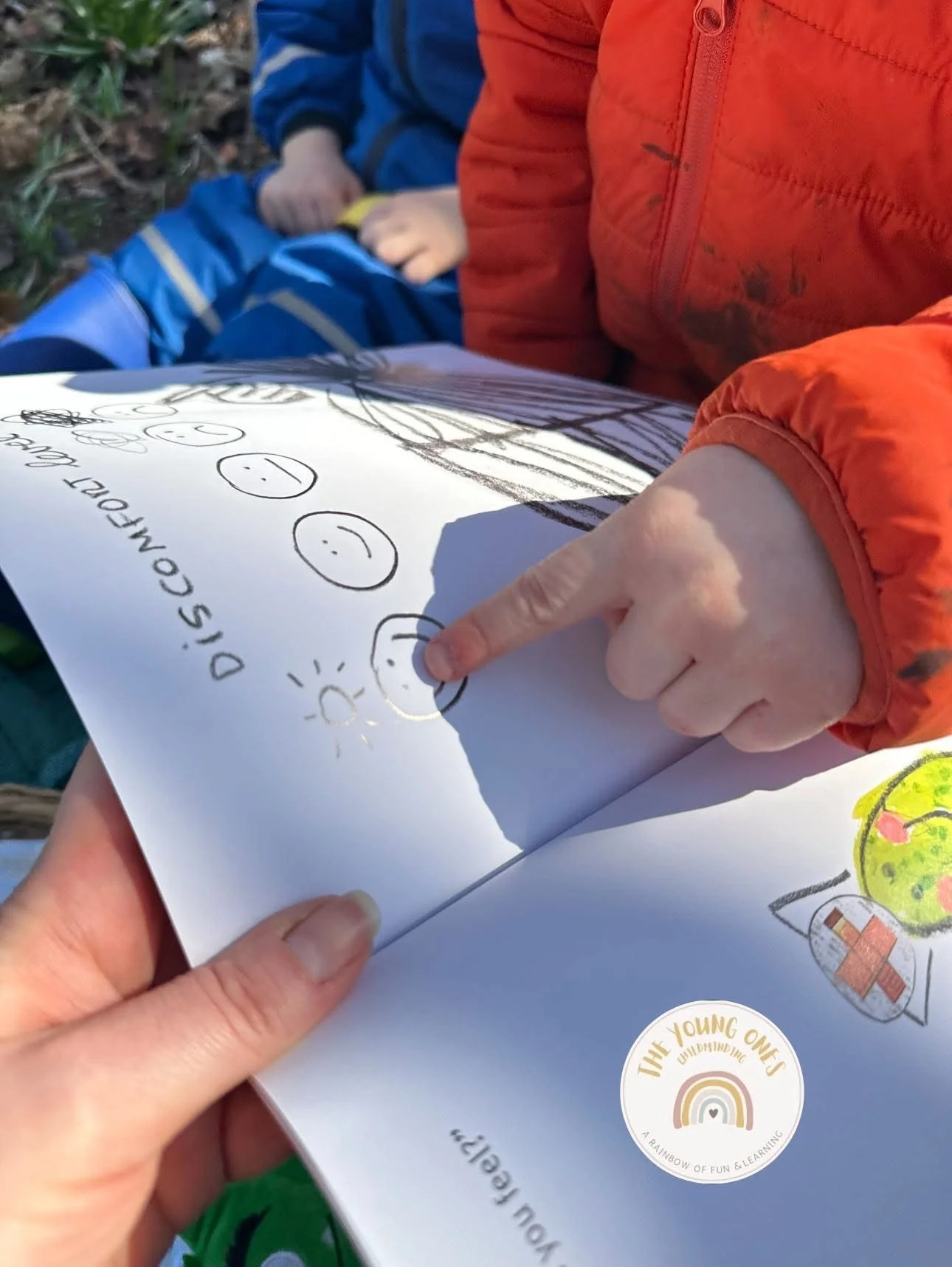

Transitions in early childhood are not limited to school. They include daily separations, changes in routine, family circumstances, emotional regulation, food relationships, and the subtle shifts that occur as children grow. I have supported children navigating anxiety, food avoidance, and additional emotional needs, and have seen how slowing down, reducing pressure, and prioritising trust can be far more effective than rushing towards outcomes.

Nature and outdoor play also play a significant role. In natural spaces, children often find calm, regulation, and confidence. The rhythm of the outdoors — seasons, weather, movement — offers a counterbalance to the fast pace of modern childhood, supporting emotional resilience and wellbeing.

Technology is part of this landscape too. Children’s lives are increasingly shaped by fast-paced digital environments, while adults are influenced by social media and high-pressure narratives that can create unrealistic expectations of childhood and early years practice. This can quietly reinforce the idea that we should be doing more, achieving sooner, and performing success — even when that doesn’t align with children’s developmental or emotional needs.

Across early years contexts, it is the quality and continuity of relationships that consistently emerge as protective factors during times of transition. When practitioners truly know a child — their interests, comforts, fears, rhythms, and ways of learning — children are more able to feel safe, regulate emotionally, and engage deeply in play. It is within these relationships that meaningful learning happens, not as something imposed, but as something lived and experienced.

Learning through play is central to this. When children are given time, space, and trust, play becomes the vehicle through which they explore ideas, revisit experiences, and make sense of the world around them. In a culture that often prioritises sitting still, meeting targets, and fitting children into predetermined expectations, play can be undervalued — despite being one of the most powerful ways young children learn. Children are not all meant to fit into the same box, and many thrive when learning is active, embodied, relational, and rooted in movement and curiosity.

Central to this is practitioner wellbeing. Children borrow regulation from the adults around them, and the emotional climate of a setting is shaped by practitioners’ own capacity for reflection, support, and care. When adults feel held and resourced, they are better able to offer the calm, responsive presence that supports children — and families — through periods of change.

Holding onto childhood, then, is not about resisting progress, and in my setting, slow, relationship-centred care is not about doing less or lowering expectations; it is about protecting the conditions children need in order to grow well. It is about recognising that when children feel seen, heard, and valued, confidence grows, engagement deepens, and transitions — including into school — become experiences of possibility rather than pressure.

For children and families, the moments that matter most are often not the measurable ones. They are the quiet moments of connection: unhurried play, shared laughter, gentle reassurance, time spent outdoors, and relationships built on trust. These are the moments children carry with them. In a world that continually asks children to move faster and achieve sooner, early years practice has the opportunity — and perhaps the responsibility — to slow down, stay present, and hold onto childhood a little longer.

This work is informed by attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969; Ainsworth, 1963), schema theory (Athey, 2007; Nutbrown, 2011), co-regulation research (Shanker; Siegel, 2012), ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), and literature on slow pedagogy and emotionally attuned early years practice.

Georgina Young is an experienced early years professional and founder of The Young Ones Childminding and Guiding The Young Ones. Having worked across the sector in both nursery and home-based settings, she is passionate about child-led learning, emotional wellbeing, and championing the value of early years professionals. Through her reflective writing and advocacy work, Georgina aims to inspire, uplift, and give voice to the heart of the sector.

References:

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss: Volume 1 – Attachment.

Athey, C. (2007). Extending Thought in Young Children: A Parent–Teacher Partnership.

Nutbrown, C. (2011). Threads of Thinking: Young Children Learning and the Role of Early Education.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development.

Siegel, D. J. (2012). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are.

If you’re interested in this, you may also like

McNair, Lynn. J., & Papaspyropoulou, K. (2025). The impact of the ‘accelerated childhood’ culture in the UK’s ECEC: practitioners’ and policy makers’ views during a professional development course. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 33(6), 889–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2025.2452547

Vuorisalo, M., Peltoperä, K., & Lucas Revilla, Y. (2025). Pedagogical practices for the infant-toddler’s first day of transition from home care to early childhood education and care. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2025.2509125

Boylan, F., Barblett, L., Lavina, L., & Ruscoe, A. (2024). Transforming transitions to primary school: using children’s funds of knowledge and identity. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 32(4), 704–718. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2023.2291354

Oo, A. T., & Hognestad, K. (2026). Bridging kindergarten and school through play: the role of play pedagogies in supporting transitions in Norway. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2026.2614625