The impact of funding changes on the Early Years sector

By Nina Taylor

My study was perhaps more of a scoping exercise to explore how recent changes in early years funding have affected supply and demand of provision in my area. My interest was piqued having followed conversations both on social media and the wider news by organisations such as the Early Years Alliance and NDNA. Multiple sources highlighted concerns about the impact of funding changes and that increases in National Insurance rates (although laudable in many respects) could increase costs for childcare providers, ultimately leading to closures, or negatively impacting staff recruitment or retention due to higher wage costs. As a student of Early Childhood, my concern is two-fold – parents and children will have limited access to high quality childcare provision, while practitioners will see little benefit in accessing higher education programmes as their efforts are unlikely to be rewarded either in terms of increase remuneration or increased employment opportunities. As a result, efforts to increase the professional status and knowledge base of early years practitioners within the sector are likely to be thwarted by the policy that focusses more on encouraging parents back into the workplace rather than investing in high quality early childhood provision which, arguably, would have greater impact on reducing social inequalities in the future.

Research has identified the importance of early childhood education in addressing social inequalities, termed social investment (West et al., 2019). It argues that provision of high quality childcare allows parents to return to the workplace, thus increasing employment productivity, as well as supporting young children’s cognitive and non-cognitive development.

Presumably, this had some influence on the Government’s decision when, in September 2025, the ‘working families’ early entitlement offer, which provides 30 hours a week of government-funded childcare and early education over 38 weeks of the year, was extended to families of children aged nine months to two years, given that the rising cost of childcare has often been cited as preventing parents from returning to work.

In order to ascertain what has happened in my local area I used a mixed methods approach to build up a picture:

Document Analysis: Utilized discourse analysis to examine funding policy documents.

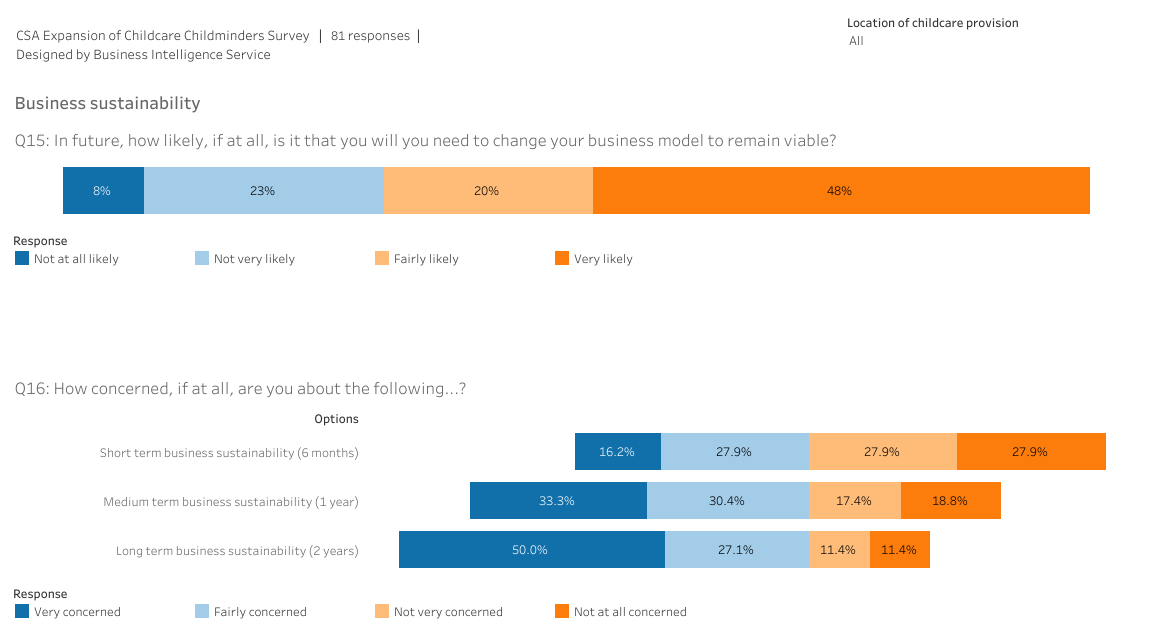

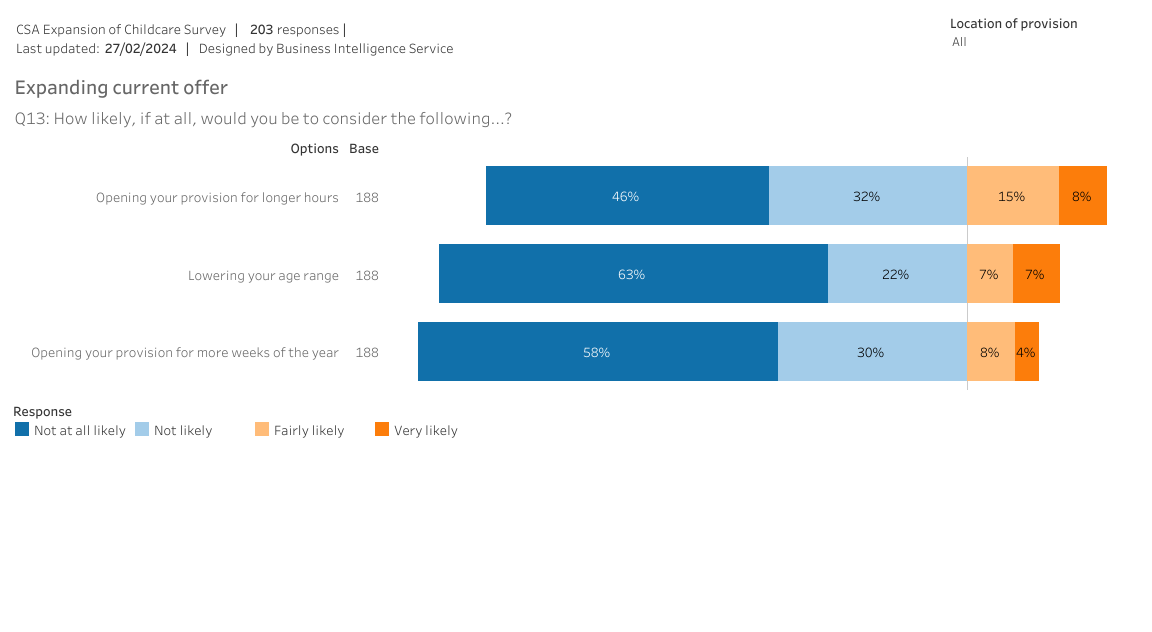

Quantitative Data: Reviewed local childcare sufficiency assessments to identify supply–demand discrepancies.

Qualitative Data: Solicited voluntary responses from parents and practitioners via a private Facebook parenting group.

Arguably, this study applies Weiss’s (1972) Theory of Change, a framework that maps how a policy intervention leads to desired outcomes through intermediate steps. Serrat (2017) describes it as a purposeful model outlining the chain of causal links from activities to results. My rationale is that the Government’s intention was to use policy intervention to allow large numbers (estimated 60,000) of parents of young children to return to work and thus boost economic productivity.

However, although I acknowledge that this is a very small scale and localised study, I would argue that my findings indicate that policy change hasn’t led to the desired result. On the contrary, it would seem that:

Local demand surpasses supply, with parents applying to multiple providers to secure places.

Practitioners report capacity constraints.

The childminder sector has experienced financial strain, with at least ten childminders ceasing operations as their businesses are no longer viable.

Example feedback from parents and practitioners via a private Facebook parenting group.

“Whether it’s to do with the funding now but trying to find a space at either a nursery or a childminders is very difficult. This time last year I really struggled to find a place for my baby for just 2 days a week. I found myself needing to find a new place last month and, again, really struggled. I went through 8 different childcare providers in my local area and all were full and had nothing to offer. Luckily, managed to find someone but not for all the days I needed, so had to sort out with family for the day I didn’t have childcare.”

“From a nursery POV - the funding has definitely had an impact. We are busier than ever. We are finding we are having to turn some parents away as we are struggling to accommodate their days or they are needing to change their working days/hours to be able to take up spaces on the limited days/sessions we have available. The amount of parents I’ve spoken to who have viewed multiple settings and they have very limited availability as well. We are having building work done to be able to meet the demand of spaces, safely. My advice to parents is definitely look round nurseries as soon as you possibly can.”

Not only has the supply of early childhood places shrunk but a review of employment opportunities locally confirms that providers are looking to recruit lower qualified staff, or even unqualified staff, which will impact the quality of provision. This reflects the finding by the Sutton Trust that "The proportion of unqualified staff working in the early years sector has risen in recent years: in 2023, 1 in 5 staff members were unqualified, up from 1 in 7 in 2018." (2024).

As result, I would argue that funding expansions intended to broaden parental employment opportunities are undermined by insufficient capacity among providers. Without ongoing operational and financial support, the sector risks transitioning back to an era focused solely on basic childcare, lacking regulation and professional development. As highlighted by the Sutton Trust, “While it is welcome that there has been so much focus on the early years in political debate, there has been far too much focus on its role as childcare, and much less on it as early education” (2024).

My poster presentation will focus on highlighting these key points and will include anecdotal vignettes from the qualitative element

Nina Taylor is a student at the Open University. You can connect with her on LinkedIn.

References

BBC News (March 2023) , Free childcare expanded to try to help parents back to work, available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-64959611

Leicestershire County Council, 2025) Audit of Sufficient childcare places, available at https://resources.leicestershire.gov.uk/education-and-children/early-years/setting-up-and-running-a-childcare-business/audit-of-sufficient-childcare-places

Serrat, O. (2017). Theories of Change. In Knowledge Solutions (pp. 237–243), available at https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-10-0983-9_24

The Sutton Trust (2024) General Election Policy Briefing Inequality in early years education, available at https://www.suttontrust.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Inequality-in-early-years-education.pdf

Weiss, C. H. (1972). Theory of Change as a Program Model. As referenced in discussions of program evaluation lineage. Available at https://www.theoryofchange.org/what-is-theory-of-change/toc-background/toc-origins/

West, A., Blome, A., & Lewis, J. (2019). What characteristics of funding, provision and regulation are associated with effective social investment in ECEC in England, France and Germany? Journal of Social Policy, 49(4), 681–704, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-social-policy/article/abs/what-characteristics-of-funding-provision-and-regulation-are-associated-with-effective-social-investment-in-ecec-in-england-france-and-germany/79A359993D1DB188E256FA30149E5E64

If you’re interested in this, you may also like

Heilala, C., Lundkvist, M., Santavirta, N., & Kalland, M. (2024). Work demands and work resources in ECEC – turnover intentions explored. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 32(3), 481–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2023.2265597

Huang, S., Zhu, Y., Liu, H., Li, X., & Pi, Z. (2025). Burnout among kindergarten teachers working long hours: causes and strategies for mitigation. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2025.2563848

Rogers, M., Dolidze, K., Mus-Rasmussen, A., Dovigo, F., & Doan, L. (2026). Early childhood educators’ understandings of quality in five countries: similarities and differences to policy. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 34(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2025.2484241