Mentoring, Communities of Practice, and Professional Identity: Exploring Apprenticeship Retention in the Early Years Sector

By Sharon Nash, Canterbury Christ Church University, United Kingdom

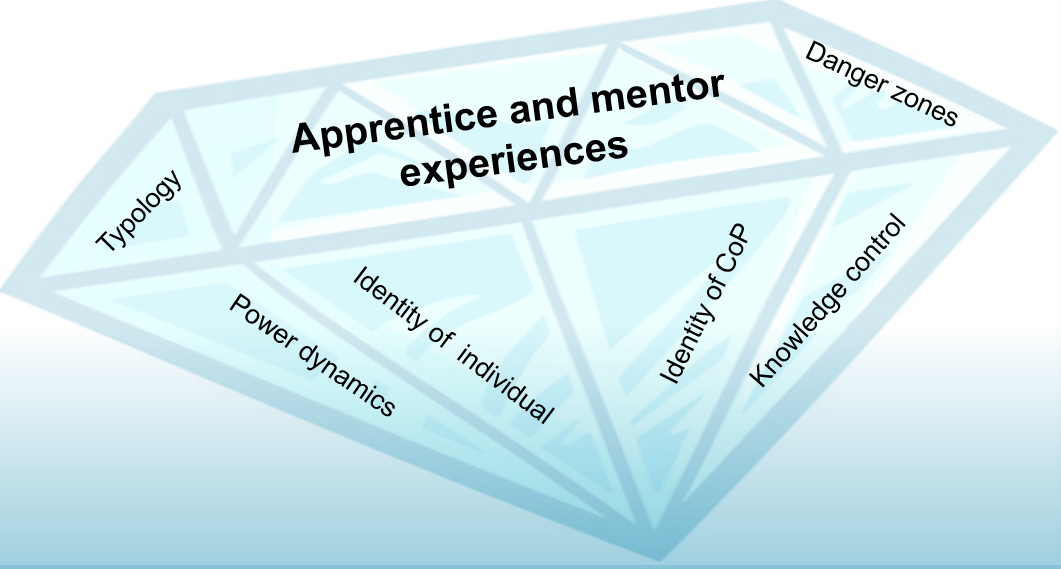

Amid concerns about retention in the early years workforce, my research focuses on how apprentices and their mentors, make sense of the mentoring process. Using community of practice literature as a conceptual lens, it will explore how these experiences contribute to their professional identity and ultimately affect their decisions to remain in or leave the profession. Underpinning this is the influence of structural forces such as marketisation, accountability frameworks, and the subtle class dynamics that shape the various communities of practice within which they work (Foucault, 1979; Smart, 1995; Foucault, Senellart, Ewald and Fontana, 2007; Osgood, 2009).

Image 1: Community of practice conceptual lens

Mentoring is recognised for supporting professional development (Glover, Jones, Thomas and Worrall, 2024) but little research addresses its role in early years apprenticeships for non-graduate practitioners (i.e. those at level 2 and 3). Working with apprentices and their mentors reignited my interest in communities of practice, including legitimate peripheral participation and identify formation (Lave and Wenger, 1991) as potential influences on the process. I then discovered the restrictive/expansive apprenticeship model of Fuller and Unwin (2003). which illuminates how workplace structures can either enable or constrain apprentices’ development and identity formation.

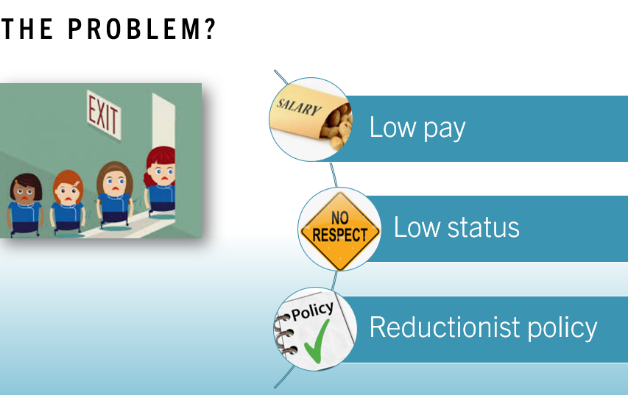

Image 2: Based on Hammond, S., Powell, S. and Smith, K. (2015) ‘Towards mentoring as feminist praxis in early childhood education and care in England’, Early Years, 35(2), pp. 139–153. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2015.1025370.

The instability of the workforce is an ongoing challenge. Turnover rates, particularly for lower qualified staff, undermine quality provision and continuity of care (Owston, Jones and Stanley, 2024). A report by the Early years Alliance (2021) found that 77% of participants cited feeling undervalued by Government as a reason for leaving. Although the Government is committed to investing and valuing early years practitioners, they remain poorly qualified with limited opportunities for progression, a lack of training, and poor working conditions. Staff continue to report feeling undervalued which further drives decisions to leave the sector (Flemons and Worth, 2025). What is really required is a highly articulate workforce with practitioners who are able to define their own professionalism and become active agents of change rather than passive recipients of policy (Traunter, 2019). Furthermore, the enhanced sense of professional identity, which this would encourage could have a positive impact on employee engagement and satisfaction with a corresponding impact on turnover intention (Wang, Xu, Zhang, and Li, 2020).

Methodology

I can’t promise a solution to the transience of the early years workforce. However, exploring lived experiences, illuminating connections and questioning norms against the backdrop of power and surveillance may challenge prevailing assumptions, contribute to sector-wide reflections and inform future policy and practice.

Like Pollert in her ethnographic study Girls, Wives, Factory Lives (1981, 2023), I want to situate micro‑level personal experiences within wider macro-level contexts to weave together individual narratives and the broader sociopolitical forces that shape them. Using an interpretative phenomenological approach (Smith, Flowers and Larkin, 2009; Alase, 2017) and collecting data through semi-structured interviews I aim to explore perceptions of the mentoring process. Simultaneously, discourse analysis will seek to uncover power dynamics embedded in policy and practice (Fairclough, 1995). This combination will provide a nuanced examination of lived experiences and how everyday situated practice is produced through, and in turn responds to, structural conditions.

Early Insights

Marketisation of the Sector

Because of their impact on the professionalisation of the sector and its workforce, my research has begun with literature exploring issues around the marketisation of education, accountability and reform.

An overview of key policy and guidance, ranging from the introduction of ‘Desirable Outcomes’ in 1996 through to further revisions of the EYFS in 2021 (Kay, 2022) indicates that although the core principles of the unique child, positive relationships and enabling environments remain intact, the shift to a technicist approach is relentless. Holistic, child-centred provision is further tempered by the quality control measures implemented by Ofsted (Ofsted, 2025).

Early years education is framed as an investment in tomorrow’s workforce (World Bank, 2018). It is idealised as a solution to social issues with children being the citizens of the future. Parents are freed up to work and contribute to the economy, jobs are created in the sector and children are equipped with skills to enable their future contributions (Moss, 2006, Gallagher, 2013). However, it is simultaneously problematised for systemic dysfunction and a deficient workforce in need of reform. This narrative haslegitimises the imposition of top-down policy, monitoring and accountability with a corresponding reduction in practitioners’ agency (Osgood, 2009: Archer, 2024; Morgan, 2025).

Professionalism and Identity

Government investment in early years education necessitates a readily available and high-quality service requiring a professional workforce. Practitioners need to possess knowledge, but also judgment and the ability to observe, interpret and respond appropriately (Kay, 2022). However, professionalism in the sector is complex when early years education continues to be perceived as not ‘real’ work, with discourses that reinforce gendered and classed assumptions (Osgood, 2009; O’Sullivan, 2015; Mooney Simmie, and Murphy, 2023; Joyce, McKenzie, Lindsay and Asi, 2025). Public perception is key to what is perceived as professional, but mostly the public do not recognise the need for special competence because the expertise required is seen as traditionally undervalued, feminine attributes (Lyons, 2012).

Practitioners are positioned within conflicting discourses encompassing their roles as enablers of school readiness, carers supporting parental employment, and providers of value for money (Osgood, 2009; Archer, 2024; Joyce et al, 2025). A desire to care for children and be of value to the community are key aspects of their identity (Payler and Locke, 2013) but there is dissonance between these relational aspects and the specific form of professionalism prescribed by the reform agenda. Practitioners have limited autonomy and control under the target-driven system with an implied mistrust of their judgment restricting their work to a technical exercise. (Ciuciu, 2023). They are seemingly undervalued in a system driven by market discourse and measurable outcomes. This can result in practitioners who conform to prescribed standards and practices (Osgood 2006: 2009; Archer, 2022, 2024).

Mentoring as a Space

Mentors can influence whether trainees accept or contest the status quo, so creating a space to critically reflect may provide a site for microresistance where apprentices and mentors challenge dominant discourse (Osgood, 2006; Hammond et al., 2015; Lyndon, 2020). This could disrupt the ‘codification’ (Foucault & Gordon, 1980:123), allowing for alternative understandings of professionalism, rebalancing power and a reclaiming of autonomy to enable practitioners to work as new professionals and initiate change.

Conference Presentation

I will present my current findings which indicate how the identity of early years practitioners can be shaped by policy, societal expectations, and market forces. Mentoring can foster confidence and professional growth; however, these benefits are contingent on workplace culture and structural conditions. For example, in settings characterised by the restrictive apprenticeship model (Fuller and Unwin, 2003) mentoring may reproduce dominant discourses of compliance and efficiency, limiting opportunities for critical reflection and autonomy.

About the Author: With a background in manufacturing and production control, Sharon Nash graduated as a mature student in Business Studies and Applied Social Science to begin a new career in education. She is now a University Instructor and PhD student; passionate about curriculum design, apprenticeships and anything Foucauldian. You can connect with her on LinkedIn and view her profile at Canterbury Christ Church University here.

References

Alase, A. (2017) The interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): A guide to a good qualitative research approach. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies, 5(2), pp. 9–19.

Archer, N. (2022) ‘“I have this subversive curriculum underneath”: Narratives of micro resistance in early childhood education’, Journal of Early Childhood Research, 20(3), pp. 431–445. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X211059907.

Archer, N. (2024) ‘Uncovering the discursive “borders” of professional identities in English early childhood workforce reform policy’, Policy Futures in Education, 22(2), pp. 187–206. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/14782103221138013.

Ciuciu, J. (2023) ‘An Ecological Exploration into the Agency of Four Former Early Childhood Teachers’, Early Childhood Education Journal, 51(8), pp. 1371–1383. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-022-01378-3.

Early Years Alliance (2021) Breaking Point: The impact of recruitment and retention challenges on the early years sector in England Available at https://www.eyalliance.org.uk/sites/default/files/breaking_point_report_early_years_alliance_2_december_2021.pdf#page=3.07 Accessed 15 November 2024

Fairclough, N. (1995) Critical discourse analysis: the critical study of language. Harlow: Longman Group Ltd.

Flemons, L. and Worth, J. (2025) The Early Years Workforce in England 2025. National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER). Available at: https://www.nfer.ac.uk/media/4uwi4cs5/the_early_years_workforce_in_england_2025.pdf.

Foucault, M. (1979) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Harmondsworth: Peregrine Books.

Foucault, M. and Gordon, C. (1980) Power/knowledge: selected interviews and other writings, 1972-1977. 1st American ed. New York: Pantheon Books.

Foucault, M., Senellart, M., Ewald, F. and Fontana, A., (2007) Security, territory, population: lectures at the Collège de France, 1977-78. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fuller, A. and Unwin, L. (2003) ‘Learning as Apprentices in the Contemporary UK Workplace: creating and managing expansive and restrictive participation’, Journal of Education and Work, 16(4). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1363908032000093012.

Gallagher, A. (2013) ‘The Politics of Childcare Provisioning: A Geographical Perspective’, Geography Compass, 7(2), pp. 161–171. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12024.

Glover, A., Jones, M., Thomas, A., Worrall, L. (2024) Finding the joy: effective mentoring in Teacher Education. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning 32, 377–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2024.2360605.

Hammond, S., Powell, S. and Smith, K. (2015) ‘Towards mentoring as feminist praxis in early childhood education and care in England’, Early Years, 35(2), pp. 139–153. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2015.1025370.

Joyce, T., McKenzie, M., Lindsay, A., Asi, D. (2025) ‘“Don’t call it a workforce, call it a profession!”: Perceptions of Scottish early years professionals on their roles from past to future’, Education 3-13, 53(3), pp. 442–455. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2023.2203166.

Kay, L. (2022) ‘“What works” and for whom? Bold Beginnings and the construction of the school ready child’, Journal of Early Childhood Research, 20(2), pp. 172–184. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X211052791.

Lyndon, S. (2020) ‘Early years practitioners’ personal and professional narratives of poverty’, International Journal of Early Years Education, 30, pp. 1–14. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2020.1782175.

Lyons, M. (2012) ‘The Professionalization of Children’s Services in Australia’, Journal of Sociology, 48(2), pp. 115–131. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783311407945.

Mooney Simmie, G. and Murphy, D. (2023) ‘Professionalisation of early childhood education and care practitioners: Working conditions in Ireland’, Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 24(3), pp. 239–253. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/14639491211010187.

Morgan, S. (2025) Stephen Morgan, Minister for Early Education: Building something better, Nursery World. Available at: https://www.nurseryworld.co.uk/content/opinion/stephen-morgan-minister-for-early-education-building-something-better/.

Moss, P. (2006) ‘Structures, Understandings and Discourses: Possibilities for Re-Envisioning the Early Childhood Worker’, Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 7(1), pp. 30–41. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2006.7.1.30.

Ofsted (2025) Annual Report 2024/25: Education, Children’s Services and Skills. London: Ofsted. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ofsted-annual-report-202425-education-childrens-services-and-skills.

Osgood, J. (2006) ‘Deconstructing Professionalism in Early Childhood Education: Resisting the Regulatory Gaze’, Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 7(1), pp. 5–14. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2006.7.1.5.

Osgood, J. (2009) ‘Childcare workforce reform in England and “the early years professional”: a critical discourse analysis’, Journal of Education Policy [Preprint]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930903244557.

O’Sullivan, J. (2015) ‘An Exploration of Poor Pay and Low Status within the Early childhood Care and Education Sector’, The OMEP Ireland Journal of Early Childhood Studies, 9(1).

Owston, L., Jones, A. and Stanley, Y. (2024) Maintaining quality early years provision in the face of workforce challenges – Ofsted: early years, GOV.UK. Available at: https://earlyyears.blog.gov.uk/2024/05/13/maintaining-quality-early-years-provision-in-the-face-of-workforce-challenges/.

Payler, J.K. and Locke, R. (2013) ‘Disrupting communities of practice? How “reluctant” practitioners view early years workforce reform in England’, European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 21(1), pp. 125–137. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2012.760340.

Pollert, A. (1981) Girls, Wives, Factory Lives. London: Macmillan.

Pollert, A. (2023) ‘Girls, Wives, Factory Lives: Fifty Years On’, Historical Studies in Industrial Relations, 44(1), pp. 131–172. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3828/hsir.2023.44.9.

Smart, B. (1995) Michel Foucault, London: Routledge.

Smith, J.A., Flowers, P. and Larkin, M. (2009) Interpretative phenomenological analysis : theory, method and research. London: SAGE. Available at: http://bvbr.bib-bvb.de:8991/F?func=service&doc_library=BVB01&doc_number=016594653&line_number=0001&func_code=DB_RECORDS&service_type=MEDIA http://www.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy1105/2009924133-d.html.

Traunter, J. (2019) ‘Reconceptualising early years teacher training: policy, professionalism and integrity’, Education 3-13. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03004279.2019.1622498.

Wang, C., Xu, J., Zhang, T.C., Li, Q.M. (2020) ‘Effects of professional identity on turnover intention in China’s hotel employees: The mediating role of employee engagement and job satisfaction’, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, pp. 10–22. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.07.002.

World Bank (2018) World Development Report 2018: Learning to Realize Education’s Promise. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2018.